what was the main cause for reducing the legal voting age to 18

:focal(487x262:488x263)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/75/e4/75e44ddb-8ad6-4c66-9fb5-f60a9023ab39/opener.jpg)

Equally the doubtfulness over the outcome of the 2020 presidential ballot sorted itself out, one data indicate was clear as twenty-four hour period: The racially diverse youth vote was "instrumental" in sending former Vice President Joe Biden and Senator Kamala Harris to the White House. According to researchers at Tufts Academy'due south Heart for Information and Research on Civic Learning and Engagement (CIRCLE), young voters aged 18-29 preferred the Democratic ticket by a 25-indicate margin. Their cohort, especially immature people of color, played a fundamental role in "flipping" battleground states including Georgia, Michigan and Pennsylvania, and the estimated youth turnout increased significantly from 2016.

Given such numbers, information technology'due south not surprising that the misbegotten impression holds today that the younger the electorate, the more than favorable the electorate for liberals. Simply the decades-long push to lower the voting age from 21 to 18, which culminated in the 1971 ratification of the 26th Amendment, came about because young Americans of different races, genders and political persuasions came together, taking on an ambivalent and resistant government, to proceeds the right to vote.

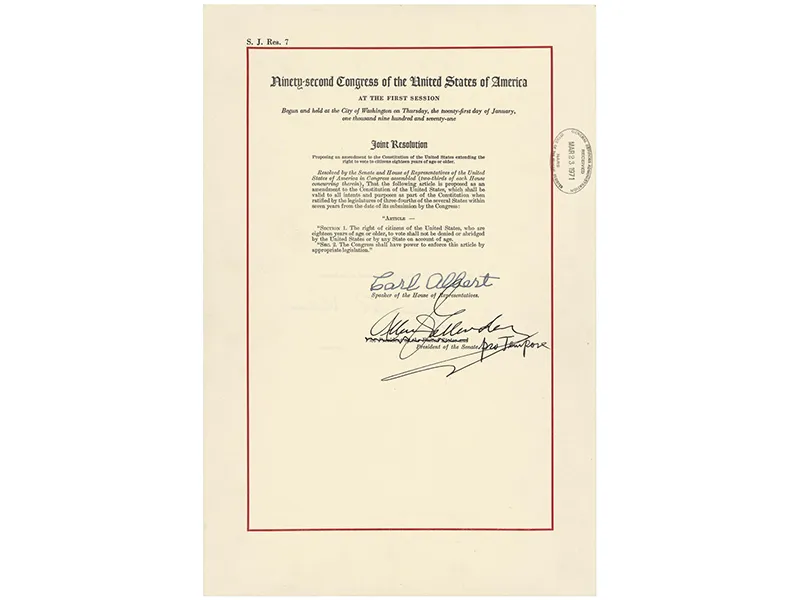

Passed by Congress on March 23 and ratified by the required 38 states by July 1, the amendment became police force in 100 days, the fastest road to ratification of any of the 27 amendments to the Constitution. Information technology declared "The right of citizens of the United States, who are eighteen years of age or older, to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the U.s. or whatsoever state on account of historic period." Ten one thousand thousand new voters were now enfranchised. Many historians and journalists have attributed the Amendment's passage to the work of anti-state of war protesters of the 1960s, who could exist conscripted into military service at eighteen but could non vote until 21. But the existent history is more layered than that.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/ca/c2/cac28d10-593b-4421-aaf6-961e0cbe35d0/gettyimages-515574892.jpg)

"It was a perfect storm in many ways," says Seth Blumenthal, a senior lecturer at Boston University and the author of Children of the Silent Majority: Youth Politics and the Rise of the Republican Party, 1968-1980 . Blumenthal notes that the tragedy of Kent Country in 1970 had exacerbated nationwide tensions around the generation gap. "America," he says, "needed a steam valve. All the sides saw means in which [the youth vote] would exist beneficial and work" for them.

The fight to lower the voting historic period began in earnest decades earlier, in the early 1940s, in response to a different conflict: Earth War Two. Between 1940 and 1942, Congress passed successive Selective Service laws that lowered the military draft age first from 21 to 20, then from xx to 18 in 1942. The 1942 age limit sparked debate in Congress near the connection between the voting age of 21 and the age of military service, and the fairness of conscripting men into service who could not vote.

"If young men are to be drafted at 18 years of age to fight for their Government," said Senator Arthur Vandenberg of Michigan as Congress considered his bill to lower the voting age, "they ought to be entitled to vote at eighteen years of age for the kind of government for which they are best satisfied to fight."

Legislators introduced multiple bills into the state and federal legislatures calling for a lower voting age, merely despite growing awareness of the issue in public and the endorsement of the cause past Offset Lady Eleanor Roosevelt, none passed at the federal level.

One obstacle, says Jenny Diamond Cheng, a lecturer at Vanderbilt Law School, was Representative Emanuel Celler, who wielded power in the Business firm Judiciary Commission. He became chair of that committee in 1949 and consistently worked to stop whatever bills lowering the voting age, which he vehemently opposed.

Another outcome: how American culture viewed teens and those in their early 20s, says Rebecca de Schweinitz, a history professor at Brigham Young Academy working on a book most youth suffrage. Most youth advocates, she says, were adult social reformers focused on creating greater access to secondary education, regulating child labor and providing services like welfare to young people. These reformers did not "talk about immature people as independent agents," who could handle the demands of adulthood, says de Schweinitz. "They talked and thought about them every bit people who needed to be cared for."

Youth themselves were besides not enthusiastic nigh gaining the right to vote. Polls, such as one covered in the Atlanta Constitution , showed 53 percent of American high school students opposed the proposal in 1943.

"This 'caretaking' understanding of young people and their rights dominated 1940s and 1950s public soapbox and policy, making information technology difficult for Vote eighteen allies to discuss 18-year-olds as independent contributors to the country" and therefore worthy recipients of the right to vote, explains de Schweinitz in her commodity "The Proper Historic period for Suffrage."

At the country level, still, the button for youth suffrage gained some momentum. Betwixt 1942 and 1944, 31 states proposed lowering the voting age, political scientist Melanie Jean Springer writes in the Journal of Policy History . Near failed, but one succeeded—in Baronial 1943, Georgia governor Ellis Arnall oversaw the ratification of an subpoena to Georgia's state constitution that lowered the voting age from 21 to eighteen. He invoked what Cheng and other scholars believe was the first use of the slogan "old plenty to fight, old plenty to vote" by a public official. Georgia would remain the only land to take the plunge for the next 12 years.

The idea simmered on the political backburner throughout the next two decades. In his 1954 State of the Union Address, President Dwight D. Eisenhower spoke in favor of lowering the voting age. By 1960, Kentucky, Alaska and Hawaii had joined Georgia in granting the vote to those nether 21 for state and local elections. (Kentucky lowered the voting age to 18 in 1955, and Alaska and Hawaii lowered the voting age to 19 and 20 respectively when they became states in 1959.) In 1963, President John F. Kennedy created the President's Commission on Registration and Voting Participation to assist counter the U.S.'southward low voter turnout in comparison to other Western countries like Denmark (at 85.5 percentage) and Italy (at 92 percent). The committee recommended solutions such equally expanding voter registration dates, abolishing poll taxes, making mail-in absentee voting easier and that "voting by persons eighteen years of historic period should be considered past u.s.."

As the U.S. government committed more than troops to the war in Vietnam, the "former enough to fight, old enough to vote" slogan re-emerged in Congress and in pop civilization with fifty-fifty more than force. At the same time, teenagers, who represented the earliest members of the large Infant Boomer generation, heavily involved themselves in political movements like the button for civil rights, campus free spoken language and women's liberation. These flashpoints stood front and center in the public consciousness, showcasing the growing ability of youth in directing the nation's cultural conversations.

Politicians "who were supporting a lower voting historic period in the 1940s and 1950s talked about the potential for immature people to be politically engaged. In the late 1960s, they didn't talk nigh political potential, considering [youth] everywhere" were engaged, says de Schweinitz.

Into the 1960s, more politicians from both sides of the aisle took a public stand up in favor of the movement. And by 1968, according to a Gallup poll, two-thirds of Americans agreed that "persons 18, 19, and xx years former should exist permitted to vote."

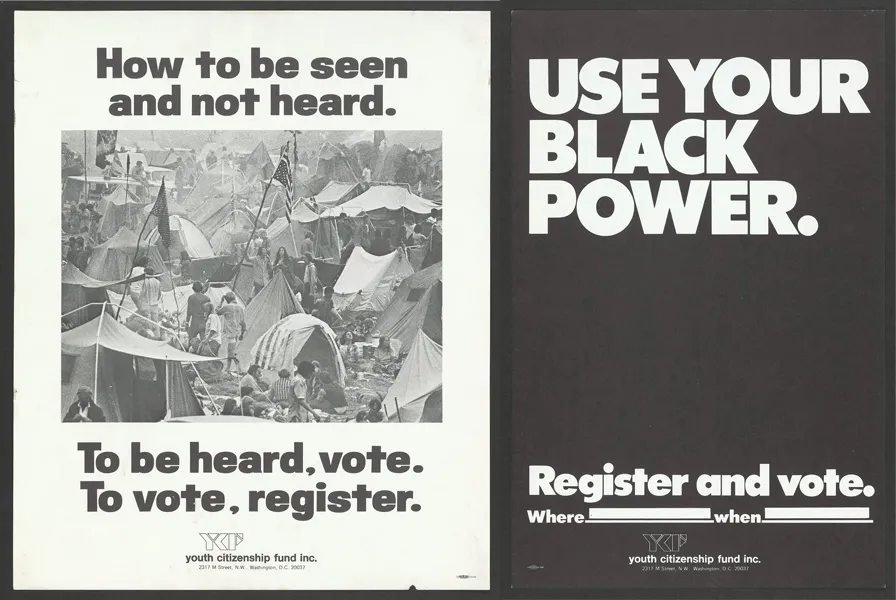

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/fd/49/fd494555-73de-4f16-ba2a-b140ac748ca7/gettyimages-515572108.jpg)

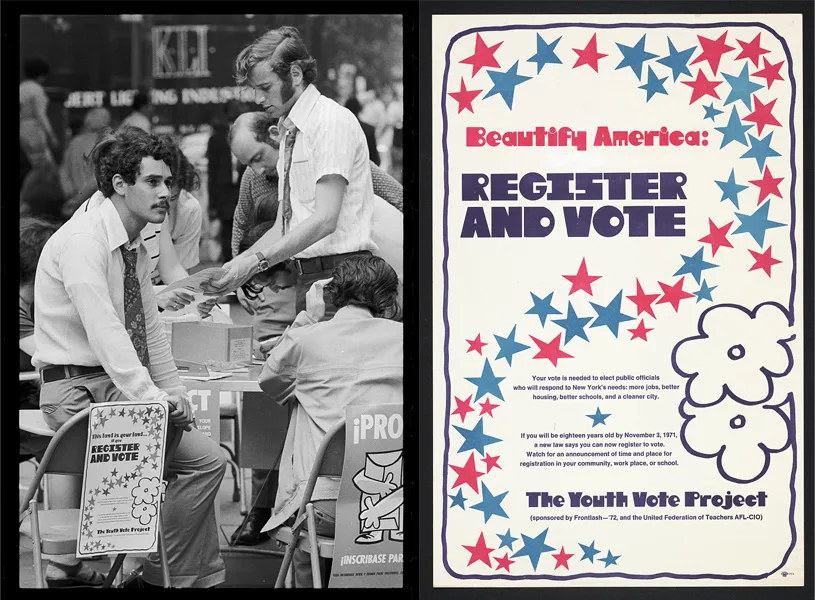

Youth suffrage became a unifying cause for various political interests, including the NAACP, Young Democrats and Immature Republicans. Some groups had lobbied for the crusade on their own, only in 1969, the activists seized on the rising tide of youth ability in all areas of civil rights and brought their cause to Congress. The coalition enjoyed the support of established unions and lobbying groups, including the United Auto Workers and the National Pedagogy Clan. The teachers' union fifty-fifty created specialized advocacy groups for the campaign: Project eighteen and the Youth Franchise Coalition.

"They brought this network together and immune people across the country to share ideas and piece of work together on a national strategy," says de Schweinitz.

The coalition converged in belatedly April that yr for the NAACP-sponsored Youth Mobilization conference in Washington, D.C. Organized by Carolyn Quilloin (now Coleman), who had started her activism piece of work every bit a teenager protesting segregation in Savannah, Georgia, the gathering brought together 2,000 young people from 33 states to lobby Congress in back up of youth voting rights.

Information technology was "a coming out effect" for the coalition, says de Schweinitz. Dissimilar earlier suffrage efforts that lacked grassroots back up, the coalition "made visible a range of land committees and organizations where young people were pushing for the correct to vote. [They wanted] to change the narrative and show that young people wanted to be full participants."

In a forthcoming commodity in the Seattle University Police force Review, Mae C. Quinn, a constabulary professor at the University of the District of Columbia and the manager of their Youth Justice and Appeals Project, writes that despite Quilloin's feel as a leader, her foundational work soon was overshadowed by three young white men lobbying on behalf of the NEA. According to Quinn's research, the white lobbyists received more than press coverage and were oft referred to as "leaders" of the national youth voting movement.

"Young black women and teens are historical subjects who don't often go talked nigh and even so have been very powerful and at the forefront of change," says Quinn in an interview. "The 26th Amendment is a place where we see that front and center, and it's of import for u.s. to retrieve that."

Scholars disagree over the extent to which grassroots activeness on voting propelled the government to act. But following the mobilization, the political wheels began to turn on making youth enfranchisement a reality. According to Blumenthal, the potential capture of the youth electorate appealed to both parties. For Democrats, it offered a chance to expand their voting base, which had suffered when the Due south defected to the George Wallace campaign in 1968. For Republicans, lowering the voting age offered a fashion to invite youth participation into the current system while keeping the status quo and preventing more radical unrest.

The Nixon entrada, gearing up for the 1972 election, wanted to ship a message that he could calm the generation gap by passing the 26th Subpoena, says Blumenthal. "Youth rebellion had become a number one concern across the country, and to send [this] message… fit into Nixon's larger message of law and social club."

This approach was echoed in a 1968 testimony before the Senate Judiciary Committee on the issue from Jack McDonald of the Young Republican National Federation. McDonald said lowering the voting historic period was a mode to give conservative youth a political vocalism and bust the myth that immature people were all disillusioned, vehement and radical. "Immature America's is a voice that says, 'Work a solid day' far more than it says 'Take an LSD trip.' Information technology is a voice that urges united states of america to 'Build man build' rather than 'Burn baby burn,'" he said.

When the commission convened on the effect again in 1970, more than members of the coalition spoke in favor of youth suffrage, bolstered by the success of the previous year'southward summit. "Many of the problems erupting from my generation today stem from frustration and disillusionment," said Charles Gonzales, a college pupil and president of the Educatee NEA. "Nosotros are frustrated with a system that propagandizes the merits of the democratic process… so postpones meaningful involvement for the states in that process."

In his testimony, James Brown Jr. of the NAACP made an explicit connection between the voting rights of black Americans and those of young people, saying: "The NAACP has a long and glorious history of seeking to redress grievances of the blacks, the poor, the downtrodden, and the 'victims' of unfair and illegal actions and deeds. The disenfranchisement of approximately ten meg young Americans deserves, warrants and demands the attention of the NAACP."

The testimonies of coalition members prompted a wave of activity on the issue. Within the month, the Senate had amended that year'south extension of the Voting Rights Deed to give the right to vote to those between 18 and 21 years of age. It was a strategic move to become around Celler, who nonetheless strongly opposed youth suffrage because he felt immature people were not mature enough to make sound political judgements, but was too an original sponsor of the Voting Rights Human action. Despite Celler's assertion that he would fight the measure out "come hell or high water," his commitment to civil rights won out.

Congress approved the alter, but Oregon, Idaho, Texas and Arizona challenged the ruling in forepart of the Supreme Court equally an infringement on states' rights to manage voting. In Oregon v. Mitchell, the court adamant that Congress could pass a change in the voting age at the federal level, but not at the state level.

This decision meant state election officials in nearly every land would need to create and maintain ii sets of voter records, resulting in a huge administrative burden and massive costs that many states did not want to have on. And even if they did, it was unlikely that everything could be organized earlier the 1972 election. This effect helped push button the 26th Amendment forward as a viable and necessary ready.

In response, the House and Senate, supported by Nixon, introduced what would become the 26th Amendment in March 1971. Fifty-fifty Celler saw the writing on the wall, telling his fellow House members: "This movement for voting by youths cannot exist squashed. Any effort to stop the wave for the 18- year-old vote would be as useless as a telescope to a blind man." Within an hour of its passage, states began to ratify the proposal. With the necessary ii-thirds majority reached on July 1, President Nixon certified the 26th Amendment four days later, saying: "The country needs an infusion of new spirits from time to time… I sense that we can have conviction that America's new votes will provide what this country needs."

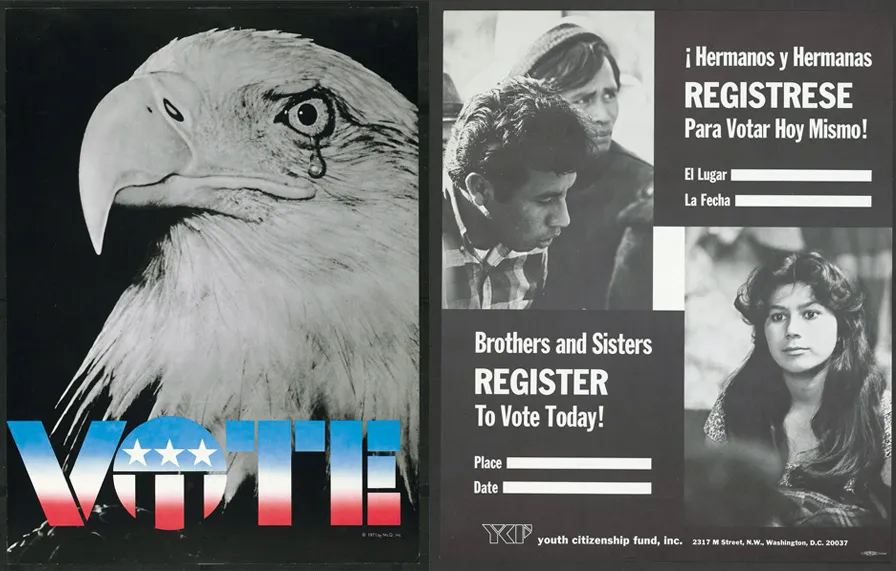

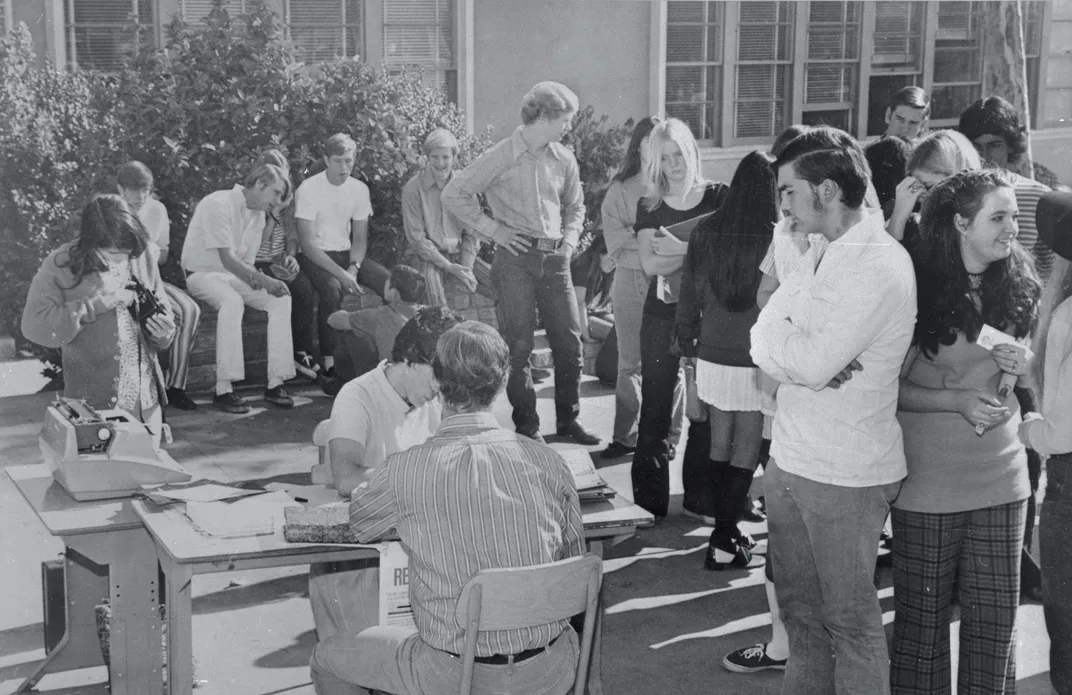

Post-obit their victory, many of the people involved in the campaign immediately turned their attention to registering new voters in time for the next year'due south presidential election. Politicians as well mobilized to capture the 18-to-21-year-old demographic. Despite widespread assumptions that youth skewed overwhelmingly left, the Nixon entrada created Young Voters for the President, an organizing arm that specifically targeted the conservative "children of the silent bulk" who didn't chronicle to the more liberal protesters and resented their clan with the youth suffrage campaign. Democratic nominee George McGovern causeless youth would overwhelmingly back up his anti-war message, and anticipated a 70 percent sweep of the demographic.

When the ballots were bandage, only well-nigh half of newly eligible youth voters turned out, and the vote was divide between the two candidates. It was a disappointing consequence for McGovern, and for many of the advocates, who had hoped for a higher turnout.

A few factors influenced the relatively low showing for youth, says Blumenthal. Registration was hampered by circuitous rules, and the sense among young people that the political arrangement was broken squashed enthusiasm to participate in the election. McGovern, also, lost steam with youth when he started highly-seasoned to older, more moderate voters as the entrada wore on.

"Even though young people didn't turn out the fashion people had hoped in 1972, the threat of them turning out forced politicians to listen to their demands," says Blumenthal, noting that Nixon pledged to end the draft in 1968 and enacted environmental protections following his victories.

Nixon'due south certification of the 26th Amendment "was the culmination of a very public [process] to demonstrate, as much as possible, to immature people that older people were set up to listen," he says. "And to some extent, it was true."

Half a century afterwards, many elements of youth voting expect similar to how they did in the 1970s: Younger voters identify equally political independents in college numbers than those in older generations practise, and they still face voter registration roadblocks and a lack of understanding around voting laws. According to Quinn, one such barrier is the overcriminalization of youth of colour, which tin atomic number 82 to developed felony convictions disallowment voting for life, fees that must be cleared before voting, and abort issuances for low-level offenses that can deter would-be voters from coming to polling places. Residency requirements and state ID laws also dampen higher students' power to cast ballots. Many of these restrictions are being contested across the state.

"Claims that young people do non vote because they are apathetic, or unconcerned about the world around them, neglect to appreciate the complication of the situations they face," Quinn, Caridad Dominguez, Chelsey Omega, Abrafi Osei-Kofi and Carlye Owens write in the Akron Law Review.

According to the Circle data, youth turnout increased in 2020 past an estimated seven percentage points over the 2016 information, a substantial increment.

Now, a new wave of activists has taken upward the mantle of youth suffrage again, this time arguing for an fifty-fifty lower voting age: 16. In some municipalities, such as Takoma Park, Maryland, and Berkeley, California, 16-yr-olds can already vote for (respectively) metropolis government and school board seats. Young people are also agile in voter registration and mobilization efforts across the country as they fight the firsthand crises of climate change, racism and economic inequality. Those spearheading today'due south youth suffrage movements can encounter their ain motivations in the words of Philomena Queen, the youth chair of the Middle Atlantic Region of the NAACP, who spoke in front of the Senate Subcommittee on Ramble Amendments in 1970:

"We see in our guild wrongs which nosotros want to brand right; nosotros see imperfections that we want to make perfect; we dream of things that should be done only are not; we dream of things that have never been done, and nosotros wonder why not. And nigh of all, we view all of these every bit conditions that we want to modify, merely cannot. You have disarmed u.s.a. of the almost constructive and potent weapon of a democratic system—the vote."

snellingcouttepore.blogspot.com

Source: https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/how-young-activists-got-18-year-olds-right-vote-record-time-180976261/

0 Response to "what was the main cause for reducing the legal voting age to 18"

Post a Comment